The Crack of Dawn #801

11/11/2025

11/11/2025

Newsletter #801

The Crack of Dawn

Collaborating is a bitch. I don’t even like the word “collaborate.” In my mind, a collaborator is one who works with the enemy. Collaborators are shot. I hear “collaborator” and my mind goes directly to Claude Rains playing the French police officer, Captain Louis Renault, in Casablanca. (The fiftieth time I saw the movie it hit me that three of the lead characters are named after automobiles: Captain Renault, Sidney Greenstreet is Ferrari, and Peter Lorre is Ugarte, pronounced oo-gartee, which sounds suspiciously like Bugatti). Anyway, Captain Renault (who has the best lines in the movie) is, for all intents and purposes, a collaborator with the Nazis. Renault is a government official working for what was then known as the Vichy government—the puppet government of the conquering Nazis.

In the last scene of Casablanca, Captain Renault grabs a bottle of mineral water and looks at the label. It’s Vichy water, a well-known effervescent beverage of the time. Renault disgustedly drops the bottle in the trash, then kicks over the trashcan. This is Louis’ moment of decision, which sets up the very end of the movie. Here is the script of the very last scene, written by Howard Koch, and Phillip and Julius Epstein (Koch and the Epstein brothers did not collaborate).

Renault walks inside the hangar, picks up a bottle of Vichy water, and opens it.

RENAULT

Well, Rick, you’re not only a

sentimentalist, but you’ve become a

patriot.RICK

Maybe, but it seemed like a good

time to start.RENAULT

I think perhaps you’re right.

As he pours the water into a glass, Renault sees the Vichy label and quickly DROPS the bottle into a trash basket which he then KICKS over.

He walks over and stands beside Rick. They both watch the plane take off, maintaining their gaze until it disappears into the clouds.

Rick and Louis slowly walk away from the hangar toward the runway.

RENAULT

It might be a good idea for you to

disappear from Casablanca for a while.

There’s a Free French garrison over

at Brazzaville. I could be induced

to arrange a passage.RICK

My letter of transit? I could use a

trip. But it doesn’t make any

difference about our bet. You still

owe me ten thousand francs.RENAULT

And that ten thousand francs should

pay our expenses.RICK

Our expenses?RENAULT

Uh huh.RICK

Louis, I think this is the beginning

of a beautiful friendship.

The two walk off together into the night.

FADE OUT:

THE END

Brazzaville, by the way, was the capital of the Congo when it was under French colonization. Congo then became Zaire, then became the Democratic Republic of Congo. In any case, that’s what I think about when I hear the word “collaborator.”

Nevertheless, collaborator is the correct word, and it’s a bitch. In my case, I’m referring to co-writing scripts, and now songs (oddly enough). I’ve had a number of collaborators over the years. What’s interesting, I find, is that even though most of these collaborations ended in recrimination and animosity; the work itself was often good. The act of having two minds focused on the same issue, or scene, or line, simultaneously, occasionally creates something new. New doesn’t necessarily mean good, but coming up with something new does move the process along. However, putting two minds together is like putting to spinning wheels together—they may or may not create ideas; but they’ll certainly create friction. Sufficient friction inevitably creates fire.

My mind drifts back . . .

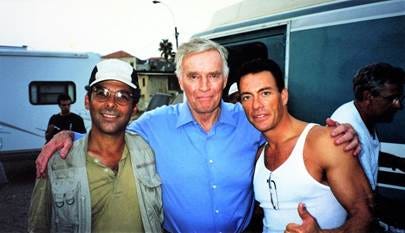

My first writing collaboration was with my old pal, Sheldon Lettich, who went on to a very successful career, making many of Jean-Claude Van Damme’s films, as well as co-writing Rambo III. Anyway, this was in 1979, before all that stuff, when we were young, dumb, and full of cum. I was twenty-one and Sheldon was twenty-eight. We were both wannabe screenwriters and directors, just starting out. Neither of us had figured out what the hell we were doing, yet, but we were trying as hard as we could. So Sheldon and I were constantly kicking around movie ideas, specifically for low-budget action movies, which we both wanted to make.

I lived in a one-room efficiency apartment, with a fold-down Murphy bed, in the foothills of the Hollywood Hills, at 1933 Whitely Ave. I didn’t have a car. Sheldon’s classy, Beverly Hills girlfriend, Evyonne, loaned me her old bike—a perfectly functional, girl’s, Schwinn, 10-speed. Hollywood has two sections: the Hollywood Hills; and the “flats.” Hollywood Boulevard is the northern-most edge of the flats; and it’s level. Going north up to the next main street, Franklin Ave., there’s a noticeable upgrade.

Proceeding north across Franklin, the no-shit hills begin. My building was near the top of the first block going up the hill. I was twenty-one, in the best shape of my life, and I could not make it up that fucking hill to my building to save my life. Not once in a year. It was discouraging.

As was Sheldon’s and my routine at the time, he picked me up in his little Nissan pickup truck, then we went to one of the many diners and low-end restaurants in the immediate area. Being a native, Sheldon knew them all. He was particularly fond of the Carnation Restaurant—owned by the condensed milk people—on Wilshire, just east of La Brea. On the corner of Wilshire and La Brea was the Mutual of Omaha building—a cool, 1930, Art Deco skyscraper (thirteen stories, actually). In the near future, Sheldon’s office, Hard Corps Productions, was located in that building for years.

Anyway, back at the Carnation Restaurant (which, I found out later, was David Lynch’s favorite haunt at that same time. David Lynch had just made Eraserhead [1978]. Coincidentally, Sheldon and Lynch just missed each other as students at the newly-opened American Film Institute). Seated in a booth, drinking coffee, me smoking a cigarette, I said to Sheldon, “This is probably a stupid idea, but how about the Marines versus the Manson Family?”

Since Sheldon had been in the Marine Corps, the idea had that going for it. Sheldon burst out laughing—apparently, he found it as ludicrous as I had. Highly amused, Sheldon suggested, “It should be called Bloodbath.” I said, “That’s kind of a cool title.” Since I’d given it a bit of thought before pitching it, I added that the story would take place in 1969 (the year Sheldon was in Vietnam), because that’s when Manson murders occurred. Adding all of the details I had, I said, “The Marines were pulled out of Vietnam in 1969, as you well know. So it would be about a bunch of recently discharged Marines, who somehow end up running into the Manson Family, right after the murders, but before the police get there. Then the Marines wipe out the entire Manson Family, including the Hell’s Angels who hung out with them.” We kicked it around a little bit, then dismissed it as absurd.

However, the next morning when Sheldon picked me up in his little pickup truck to go get coffee again, he was giddy. He said, “That Marines versus the Manson Family wasn’t a bad idea; it was a good idea.” Then Sheldon told me the entire story, in great detail. Clearly, he’d given this an enormous amount of thought. He knew who all these guys were, and what they’d been through, and how they felt. I was gobsmacked. Completely overwhelmed. In the course of one night, Sheldon had somehow managed to take my silly little low-budget idea, and transform it into The Deer Hunter. He could clearly see all of it.

Immediately, I was flooded with conflicting thoughts and emotions. On the one hand, Sheldon really liked my idea; on the other hand, I’d had no part in the story’s development, and that’s not how I saw it. Sheldon didn’t do this with any malice—only pure, unbridled enthusiasm—but however he did it, he’d just taken my project away from me.

End Part I.

I was there for the creation of the play, and saw the first production. The writing credit should be, Written by Sheldon Lettich, story by all those other guys. Sheldon interviewed about a dozen (maybe more) Vietnam vets, like himself, and recorded them. Then he took the giant mass of material and boiled it all down into a good play. Sheldon wrote it. Of all the first-day-in-the-service and being yelled at by the drill sergeant scenes--including "Full Metal Jacket"-- Sheldon's is the best. I memorized the speach,g, and I recently did bits of it for Sheldon. "Hiding behind the tall elephant grass you will meet Luke the gook, Link the chink, and Charlie Cong." It's great.

And Laurence Fishburn was an 18-year-old stagehand on the play.

Sheldon in the news: https://deadline.com/2025/11/tracers-documentary-matthew-perniciaro-in-works-exclusive-1236616445/?fbclid=IwY2xjawOGQKlleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFsYzEzdFc1d2J2UVpXN1dWc3J0YwZhcHBfaWQQMjIyMDM5MTc4ODIwMDg5MghjYWxsc2l0ZQEyAAEeMg6i_fwe4aXjDp9aDfco0BS9aPV4N38N2hl7LeEW3qTfnjzqy5dVM--Uwa8_aem_3hcvJo2EjX-BknslgKlFCQ

I remember you said you went to see an early production of this. :)